Numerical analysis of end-fire coupling of surface plasmon polaritons in a metal-insulator-metal waveguide using a simple photoplastic connector  Download: 790次

Download: 790次

1. INTRODUCTION

Plasmonic nanostructures enable light waveguiding beyond the diffraction limit, making them potentially useful for applications such as super-resolution imaging [1], optical communications [2], and ultrahigh-density data storage [3]. Devices based on the metal-insulator-metal (MIM) structure are among the most promising because of their ability to minimize the losses that occur during nanofocusing processes. This ability is attributed to the fact that this structure has no cutoff size; further, all the energy from the probe base can propagate to the probe aperture, and the aperture is not shielded by a metal screen. In addition, the probe can possess a large tapering angle (which leads to a small probe length) in accordance with a rapid decrease in mode wavelength with decreasing MIM waveguide height. However, devices that can support surface plasmon polaritons (SPPs) suffer from high ohmic losses in the constituent plasmonic materials (usually gold, silver, or aluminum) [4]. This reduces the propagation distance of highly confined SPPs and therefore limits the application of such devices.

Owing to the high dissipative losses, it is crucial to use an excitation configuration in which SPPs can be excited with high energy efficiency and the length of the metallic elements of the plasmonic devices can be reduced. A major concern here is the efficiency of the interface between conventional micrometer-size photonics and plasmonics with sizes of tens of nanometers. SPPs cannot be excited by a single freely propagating photon because of the momentum mismatch between freely propagating light and SPPs on the metal surface. There are other methods of SPP excitation, such as use of the Kretschmann and Otto geometries [5], end-fire coupling [6], vertical excitation [7], use of diffraction gratings [8,9], and excitation by a focused laser beam [10,11].

MIM waveguides such as the recently fabricated gap plasmon waveguide with a three-dimensional (3D) linear taper [12] can play a crucial role in future near-field investigation of the features of live cells and other objects with super-resolution, owing to their unique ability to image biological processes at the cell membrane, the site of many medically important events [13,14]. Nevertheless, excitation of the structure by direct laser irradiation requires complex and precise adjustment of the entire system. At the same time, the creation of a high-power Gaussian beam using a fiber-coupled 405-nm diode laser system [15,16] and fiber lasers [17,18] is a well-known and extensively investigated process. In this work, we propose a design for efficient end-fire coupling of SPPs in a MIM waveguide with an optical fiber as part of a photoplastic connector. Fiber coupling of the laser beam to a near-field probe allows one to move only the MIM part of a scanning near-field optical microscope during object scanning, making it possible to significantly increase the speed and working area of the microscope. The main advantage of this design is that it enables simple connection of an optical fiber to a MIM waveguide and local excitation of the waveguides with high energy efficiency. In addition, use of the design allows one to reduce the length of the metallic elements of the MIM waveguide and, therefore, reduce the dissipative losses. The design was analyzed and optimized by the 3D finite-difference time-domain (FDTD) method [19] using light with a wavelength of 405 nm. Violet light was used in the simulation because it is very informative and widely employed for analysis of biological objects [20,21].

2. DESIGN OF THE PHOTOPLASTIC CONNECTOR

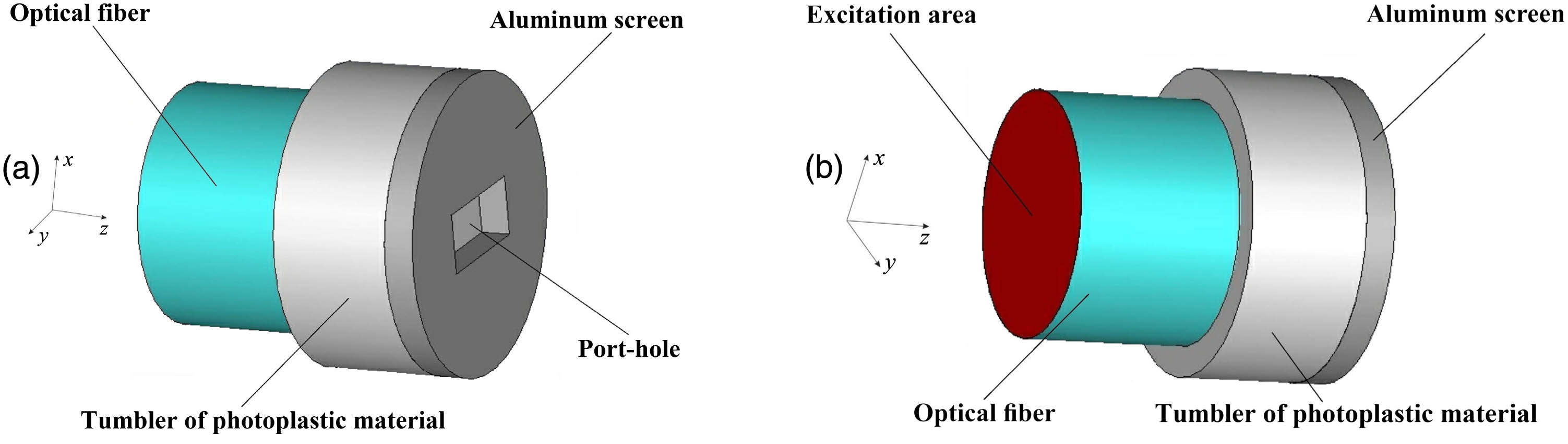

The spatial geometry of the connector is shown in Fig.

Fig. 1. Spatial geometry of the photoplastic connector: (a) view from the PH; (b) view from the excitation area.

Fig. 2. Schematic representation of the connector design: (a) view from the excitation area, (b) view from the PH, and (c) longitudinal view.

The dimensions of the PH are also such that they allow only the fundamental

3. NUMERICAL SIMULATION

3.1 A. Numerical Analysis Technique

The proposed design was numerically simulated by the 3D FDTD method [19]. The simulation was performed for light with a wavelength of 405 nm (frequency

Fig. 3. Contour plot and profiles of the absolute value of the electric field of the fundamental propagation

An optical fiber with a reduced diameter of 1 μm was used to realize the single-mode regime as nearly as possible. The

Starting from the fundamental Maxwell’s equations [29,30], the dispersion relation for the fundamental symmetric plasmon quasi-

Fig. 4. Electric field amplitude (3 .

A comparison of Figs.

The connector has a metal part that can cause significant dissipative losses. Therefore, the structure of the coupler should not have a high-

This allows us to analyze the dependence on the connector parameters of the power coupling efficiency of an optical fiber directly with the connector and of the connector with the free-space plane waves. Here, the power transmission coefficient

The MIM waveguide was then connected to the optical fiber via the PH. The coefficient of the MIM waveguide excitation efficiency,

3.2 B. Results and Discussion

Figure

Fig. 5. Dependence of

All the other waveguides, which can be considered as parts of our structure, have only a few modes, which cannot be excited owing to structural symmetry [25]. Therefore, the analysis based on the single–mode approximation can give a good first-order approximation and will be used below for the energy transmission analysis.

We can consider the inhomogeneous area between the beginning of the tumbler and free space as an open resonator connected to the fiber on one end and to free space on the other side. Weak coupling efficiency from any side of the resonator would result in high reflection for any resonator length. If the coupling efficiency from both sides of the resonator is weak, the resonance of the reflection and transmission coefficients depends strongly on the resonator length. At resonance, the transmission and reflection coefficients exhibit a large narrow peak and deep dip at lengths far from the resonance length. However, the power transmission coefficient shown in Fig.

From Eq. (

Figure

As shown in Fig.

A cross-sectional view of the electric field and energy flux in the structure is shown in Fig.

Fig. 7. Cross-sectional view of the electric field and energy flux in the structure: (a)

In the next part of the simulation, the MIM waveguide was connected to the optical fiber via the PH of the connector. Note that the optimization of the connector parameters performed earlier gives only a qualitative estimate, because connecting the MIM waveguide to the optical fiber changes the conditions at the end of the PH. In this case, the load impedance

Figure

The data in Fig.

A cross-sectional view of the electric field and energy flux in the structure with the MIM waveguide is shown in Fig.

Fig. 9. Cross-sectional view of the electric field and energy flux in the structure with the MIM waveguide: (a)

Note that when this photoplastic connector is used, the length of the waveguide base

4. EXPERIMENTAL FEASIBILITY

Although our design is based on numerical analysis, the experimental process can be discussed on the basis of some experimental works [12,22]. The photoplastic connector is fabricated as follows: (1) an oxide layer is produced on the Si wafer by thermal oxidation; (2) after deposition of a sacrificial layer, the aluminum screen is created using vacuum evaporation; (3) photoplastic material is deposited on the Al screen using a spin-coating procedure [38]; (4) the photoplastic part is then exposed to ultraviolet (UV) radiation and developed to create a tumbler for the optical fiber; (5) the optical fiber is then inserted into the tumbler and fixed using UV glue; (6) the optical fiber in the connector is separated from the wafer; (7) at the end, a PH of appropriate size is created in the Al screen by focused ion beam milling. Note that the technological requirements for manufacturing the connector can be reduced because the excitation efficiency coefficient

Note that reducing the fiber core diameter may lead to

Moreover, via the existing nanotechnologies, it is possible to create a substrate-based structure with free access to the base end face of the MIM waveguide. In addition, it has been shown [41] that the excitation efficiency is not very sensitive to the width of the incident beam and the position of its center on the MIM end face. In other words, in a real implementation, one can just connect an optical fiber to the MIM waveguide without needing to perfectly match the PH plane to the end face of the MIM waveguide.

5. CONCLUSIONS

Plasmonic nanostructures allow for light waveguiding beyond the diffraction limit, making them potentially useful for applications such as super-resolution imaging, optical communications, and ultrahigh-density data storage. Owing to the high dissipative losses in most plasmonic devices, it is crucial to excite SPPs with high energy efficiency. For this purpose, the design of efficient end-fire coupling of SPPs in a MIM waveguide with an optical fiber as part of a photoplastic connector was proposed. Detailed numerical analysis and optimization of the connector parameters were conducted. The calculated excitation efficiency coefficient of the MIM waveguide using the proposed photoplastic connector is 83.7% (

[27]

[29]

[35]

[40] J. Luo, Y. Fan, H. Zhou, W. Gu, W. Xu. Fabrication of different fine fiber tips for near field scanning optical microscopy by a simple chemical etching technique. Chin. Opt. Lett., 2007, 5: 232-234.

Article Outline

Yevhenii M. Morozov, Anatoliy S. Lapchuk, Ming-Lei Fu, Andriy A. Kryuchyn, Hao-Ran Huang, Zi-Chun Le. Numerical analysis of end-fire coupling of surface plasmon polaritons in a metal-insulator-metal waveguide using a simple photoplastic connector[J]. Photonics Research, 2018, 6(3): 03000149.